|

Connect with Laura

Sign up for Laura's

newsletter

Available for preorder:

Read an excerpt

Read an excerpt

|

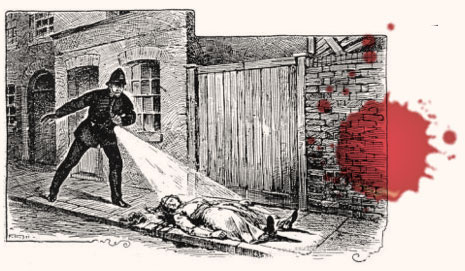

It's 1888, the year of Jack the Ripper, the most famous serial killer in history. Modern forensic

science hasn't been invented yet, and the police are powerless to stop the Ripper as he haunts the

foggy streets, brutally slays one prostitute after another, and terrifies all of London. Enter Miss

Sarah Bain, a photographer in Whitechapel, a solitary, independent woman with dark secrets. One of

her secrets is that she supplements her meager income by taking illegal "boudoir photographs" of

prostitutes. Sarah is the only person who knows that the Ripper isn't choosing his victims

randomly—he's targeting her models. As she conducts her own private investigation into

the murders, she clashes with Police Constable Barrett, who has his own personal reason for

wanting to catch the Ripper. She acquires a motley crew of friends: Lord Hugh Staunton, a

gay nobleman; Mick O'Reilly, a street urchin; Catherine Price, a budding young actress; and

Abraham Lipsky, a Jewish butcher, and his wife Rachel. They band together with Sarah to solve

the Crime of the Century. In the process, Sarah embarks on a personal journey that teaches her

the meaning of friendship and uncovers clues to the mystery of her own past.

PROLOGUE

"I never done this before," she says. "What do you want me to do?"

The flickering gas lamps illuminate her, a short, dark woman with brown curls, dressed in a threadbare brown frock and a black straw bonnet, standing by an iron bedstead. The light is cruel to her. It shows the scar on her forehead and the ugly absence of a front tooth. She fidgets with her hands, as awkward as a novice actress auditioning for her first play.

I adjust the camera on the tripod. "You can begin by undressing."

Trepidation clouds her face. "I'm not used to undressing for a woman."

"Pretend I'm a man, if it will help."

"You, miss?" She laughs, incredulous, then tosses her bonnet on the hat stand and smiles coyly in an attempt at play-acting. "A gentleman offers a lady a drink."

We both know she is no lady, and gentlemen seldom waste formalities on her. I motion to the wine bottle and glass on the bureau and say, "Please help yourself."

She drinks and licks her lips. Her face flushes, and her eyes acquire a bolder gleam. She strips down to her chemise and petticoats and bends over to unlace her shoe. "How's this?"

I aim the camera, duck under the black cloth that hangs from the back of it, and crank the bellows to focus her image in the viewfinder. "Excellent. Hold still, please." I throw off the cloth, raise the flash lamp, and open the camera's shutter.

Flash powder ignites in an explosion of white light. Shooting sparks burn my hands. I take photograph after photograph while she poses and flirts with the camera.

She leans on the iron bedstead, her bosom spilling from her corset, her round buttocks lifted, the pale, lumpy flesh of her thighs bulging out of garters and black stockings.

The room fills with acrid white smoke from the flash powder, soporific fumes from the gas lamps, and the ripe, fish-market odor of her body.

Seated on the edge of the bed, she cups her bare breasts in her hands, eyes twinkling mischievously as she tongues a coarse brown nipple.

We exchange conspiratorial smiles. The thrill of breaking the law, and pride in our daring, add spice to our clandestine business. She begins to relax and enjoy herself. I enjoy her company on what would otherwise be a long, lonely night.

Lying nude on the lace counterpane, sprawled with her knees raised and open, her fingers spreading her womanhood, she feigns an expression of rapture.

After we're finished, she dresses, and I hand her coins, an advance on her share of what the sale of the pictures will fetch.

"If you want me for more pictures, just let me know," she says. "T'is pleasanter and safer than my usual work, if you take my meaning."

I nod. Women in her profession experience terrible degradation, and danger, on the streets of Whitechapel. Better she should pass the time with me.

"There's them that would say we're sinners and God should strike us down for what we done tonight," she says. "The coppers would throw us in prison if they found us out. But I say, what's the harm in it?"

Chapter 1

The East End of London is dangerous even by daylight, and I am a solitary woman abroad at four o'clock in the morning. It is Friday, 31 August, 1888, and I have come out to photograph the sunrise over the river Thames. I position my tripod at the top of the stone staircase. I hear waves lapping, but the fog obscures the oily black water beyond a few feet from where I'm standing on the embankment. The sky glows red from a fire burning at the Shadwell Dry Dock. Smoke, ash, airborne cinders, and fog produce an atmosphere like the steam from a witch's cauldron.

As I wait for daybreak, machinery in distant factories grinds and clangs; a train whistle shrills. The city is never silent. I reach for the leather satchel beside me, which contains my miniature camera, lenses, and negative plates. Made by a brilliant, reclusive inventor, the camera cost a small fortune and is my most precious possession.

A small figure darts out of the fog, grabs the satchel, and runs. I cry out in alarm. "Stop!" I pick up my tripod and give chase.

The thief is a boy. As the distance between us widens, the fog blurs his shape. Hampered by the tripod and my long skirts, I pant after him. Grimy brick buildings materialize in the flame-tinted, smoky fog. Gas lamps along the streets glow like miniature yellow moons.

"Help!" I shout. "Thief!"

In these small hours before dawn, a few drunken men stumble along; harlots straggle toward their dosshouses; vagrants slumber in the doorways of the tenements. No one comes to my aid. The uneven cobblestone pavements are moist, slick. I trip and fall.

The boy and my satchel are vanished into the fog. I rub my bruised knee, pick myself up, and lament my carelessness. The miniature camera was one of a kind, and I can't afford to buy anything remotely similar. I trudge homeward, alone by habit and choice. A dark place inside me casts a shadow into which other people venture at their own peril. I keep my distance from them, lest their association with me should compromise them in some way—or lest my association with them should injure me.

The factory machinery pounds out a funereal rhythm as I enter Buck's Row. This narrow, cobbled lane extends like a gloomy tunnel between a line of dilapidated tenements on my right and Essex Wharf on my left. Yellow light emanates from lanterns in the midst of a crowd. People stand, their backs to me, staring down at something. At the crowd's edge, the boy with my satchel loiters.

My heart leaps. I hurry to him and grab the handle of my satchel. "That's mine! Give it back!"

The boy whirls. All knobby knees and elbows, dressed in a ragged jacket and knickers too big for him, he has an elfin face beneath spiky red hair. Freckles dash his upturned nose. I put his age at twelve years. He is one of countless street urchins who roam London. His blue eyes shine with feral intelligence.

"Hey! Let go!" He recognizes me; he's alarmed that I've caught him red-handed.

As we wage a tug-of-war, a police constable in a blue uniform and tall helmet approaches us. The boy and I freeze.

"What's the trouble, mum?" the constable asks.

If I say the boy stole my property, the constable will make him give it back. But an ingrained fear of police holds my tongue. My only, disastrous brush with them occurred twenty-two years ago—when I was a little younger than this boy. Now I see in the boy's eyes a reflection of my fear: The law is no more a street urchin's friend than it was mine. Our gazes meet. It's rare for me to feel such a mutual sense of kinship with anyone. It's rarer still that I put myself out for someone else's sake, but my instinct is to protect a child whose welfare is in my hands.

"No trouble, sir," I murmur, and let go of the satchel.

The constable looks askance at me —a thirty-two-year-old spinster. My figure is thin like a whip under the damp, threadbare gray coat that covers my modest gray frock. He can see that I am low on the scale of prosperity although better off than many in Whitechapel. My face is too sharply carved for beauty, my hazel eyes too deep, and my jaw too square. My best feature—my thick, straight ash-blond hair—is pinned up in a coronet of braids under my bonnet. Long tendrils escape the hairpins and wisp around my face no matter how much bandoline I use.

"That's good," the constable says, "because I got enough trouble already. There's been a murder, and this here's a crime scene."

As the boy flees with my satchel, I already regret that my fear of the police and a moment's compassion for the thief have cost me so dearly.

The constable marches back to the crowd, which contains many other policemen. I'm free to go home, but I linger even though I'm not interested in the murder. Murder is common in Whitechapel. Rather, my fear of the police contains an element of curiosity, of attraction. When I'm afraid—when my heart is pounding, my every nerve alert, and my body tense with the instinct to run—that is when I feel the most alive. I don't know why; I only know that I've always been this way. Life without fear is like a photograph without dark shadows to contrast with the bright objects. Danger adds a pleasurable thrill to my usually quiet, staid existence. When I see the police, it's as if I've come upon a sleeping wolf and I feel an impulse to poke it and wake it up. Inhibited by caution, yet excited by my own daring, I move toward the police.

People in the crowd shift, and I spy a woman lying on her back upon the cobblestones outside the gate of a stable. Her brown frock is raised above her knees, exposing her scuffed boots, her petticoats, and her thick legs in black stockings. I don't immediately see her face. I see only the terrible red gash across her throat. My breath catches and bile rises in my own throat. My heart thuds; I hear a roaring in my ears. I have seen death before—victims of brawls, accidents, or other murders—but never a death like this. Horrified, I want to turn away but cannot move. I stare at the grisly red flesh around the wound, the exposed blood vessels. Blood has pooled between the cobblestones, drenched the woman's clothes.

It is her clothes that I recognize first.

I saw them in my studio not a month ago, when she took them off to pose for my camera. The black straw bonnet lies near her motionless left hand. My stricken gaze travels to her face. I see the gap between the front teeth, the scar on her forehead, and I can put a name to her: Polly Nichols.

My hand flies to my mouth. I hold my breath, praying not to be sick. Through my vertigo, nausea, and faintness swims the thought, Not again.

The constable says, "Can anybody here tell me who this woman is?"

My lips part to answer, then close, sealed by my realization that I don't want him to wonder what connection I have with Polly. She was my newest model for what I call my boudoir pictures and the police call a crime.

My first model was Kate Eddowes, another woman of the streets. Some eighteen months ago Kate walked into my studio and asked me if I would photograph her. I quoted my price, and her frank description of the kind of pictures she meant shocked me. Her next words enticed: "I know a man who'll pay ten times your usual price. We'll split it. What do you say?"

I refused the first time she asked, and the second. I did not want to risk running afoul of the law, and I shied from the intimacy that this project would necessitate. The third time, I changed my mind. Customers had been few of late, my landlord had just raised my rent, and if my studio should fail, what would I do? I've no family to take me in. Looking at Kate's haggard face, I saw a future for myself as a streetwalker. And so I agreed to her scheme.

The man did buy her pictures for the sum she'd named, and he wanted more. There is a thriving black market for erotic photographs of models of all varieties. Kate brought other women to pose for me. Although our relations were strictly business, years of solitude had lately become a crushing weight on my spirits, and I appreciated the semblance of camaraderie. I found unexpected pleasure in fancying myself the women's protector, sparing them many nights in fornication with strangers on the dangerous streets of Whitechapel. A constable is asking spectators whether they knew the dead woman. Each says no, whether it's true or not. Whitechapel folks are loathe to cooperate with the police. What shall I say when my turn comes? Would that I hadn't so much to hide!

Polly isn't my first model to be murdered.

The first was Martha Tabram. She was stabbed to death some three weeks ago. At the time I thought it a random crime, a fate not rare among streetwalkers. But now that Polly has met her end in similar fashion, a chill creeps through me. Polly and Martha both stepped into my shadow and came to harm. Out of thousands of prostitutes in Whitechapel, why two of my models?

"What about you, mum?" the constable asks me. "Do you know this woman?"

I gather the presence of mind to say no. He turns to two men who wear aprons filthy with old bloodstains. He asks, "Who are you? What are you doing about at this hour?" He must suspect that the killer is among us, pretending to be an innocent observer.

The men identify themselves as horse slaughterers from Barber's Slaughterhouse, on their way to work. There are many slaughterhouses in these environs, whose reek of decayed meat taints the air. There are many bloodstained men about at any hour. My gorge rises at the rank, metallic, salty-sweet smell that issues from Polly's body. I sidle away.

"Hey! Not so fast!" the constable says, and demands to know who I am and where I live.

"Sarah Bain, 223 Commercial Street." My fear now overwhelms curiosity and attraction. Excitement and daring desert me. I stare at the ground.

"Why are you hereabouts?" he asks.

The barrier between the present and the past dissolves. I travel twenty-two years backward in time, hear other police barking questions, and for a moment I cannot find my voice. Then I remind myself that this constable can't read my mind and know anything I've done. My visage is as opaque as the fog that allowed the killer to commit his crime unnoticed. I manage to explain that I am a photographer, on my way to take pictures of the city.

"You look a bit upset, mum." I can feel the constable's stare boring into me. "Why's that, if you didn't know the woman?"

I might have said that this gruesome spectacle of death would upset anyone, but of course that's not the whole truth, and what if he guesses I'm lying by omission? The constable draws his breath, and I brace myself to hear him shout threats like those that echo in my memory.

A horse-drawn ambulance wagon rattles up to us. A doctor, wearing a long coat and derby, carrying a black medical bag, climbs out. The constable turns to greet him. I back away, blending with the crowd. I could make my escape, but I can't resist my urge to know more about what happened to Polly.

The doctor winces as he eyes her. "Let's get her to the morgue. I'll do my examination there."

The constables lift Polly; her head dangles from her severed neck. The crowd gasps. The constables load Polly into the ambulance, the crowd disperses, and two men bring mops and buckets and wash Polly's blood off the street. I retreat to the end of Buck's Row and mull over disturbing questions.

Is it a coincidence that Polly Nichols's murder followed so closely after Martha Tabram's?

What if it is not?

|